Search

Search

Asia Pacific

Europe

Latin America

Middle East & Africa

Search

Search

Asia Pacific

Europe

Latin America

Middle East & Africa

As the mainstream device for electrochemical energy storage, lithium-ion batteries are widely used in data centers. As a key indicator for measuring their performance, energy density profoundly affects various performance metrics and application scenarios. What exactly is the energy density of lithium ion battery, why is it so important, and what factors influence it?

As a key indicator for measuring the performance of lithium‑ion batteries, the energy density of lithium‑ion battery refers to the energy stored per unit volume or unit mass. This measurement is typically presented in Watt-hours per kilogram (Wh/kg). A watt-hour is a measure of electrical energy that is equivalent to the consumption of one watt for one hour. The higher the energy density, the more electrical energy can be stored in the same volume or weight, which directly improves device run‑time.

Batteries with high energy density offer significant advantages across multiple dimensions, including improved run‑time, enhanced efficiency and safety, and reduced costs. Take energy storage systems as an example:

Improving Energy Storage Duration:

With large‑scale integration of renewable energy into the grid, storage systems demand long‑duration, high‑capacity charge and discharge. High‑energy‑density batteries, by storing more power per unit volume or mass, significantly extend system run‑times.

Enhancing Efficiency:

High‑energy‑density batteries feature superior charge–discharge efficiency, enabling fast charging and high‑current discharge. This boosts response speed and power output, allowing storage systems to adapt to load changes and provide services like frequency regulation and peak shaving.

Enhancing Safety:

Modern high-energy-density batteries incorporate advanced materials and optimized structures during research, development, and manufacturing—such as highly reliable lithium iron phosphate cells and overcharge/over discharge protection circuits—to effectively reduce safety risks like thermal runaway, fire, and explosion, ensuring the stable operation of energy storage systems.

Reducing Costs:

For the same storage capacity, high‑energy‑density batteries require fewer units and less floor space, lowering construction costs. Their higher conversion efficiency minimizes energy losses and operational expenses, while longer lifespans reduce replacement frequency and maintenance costs.

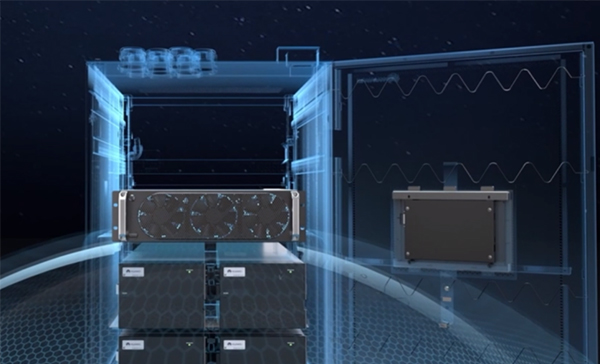

Take Huawei SmartLi Lithium Battery system for UPS as an example.

It features safety, reliability, long lifespan, space‑saving design, and ease of use. High‑density cabinets occupy less floor space, offer high discharge efficiency, and longer service life.

Huawei SmartLi Lithium Battery secures safety across five tiers—cell, module, pack, cabinet, and system.

Cell Level: Utilizes high-consistency LFP batteries that remain fireproof even when punctured, ensuring outstanding reliability.

Module Level: Features a fully plastic-insulated "aviation cabin" design to isolate micro-shorts and prevent cascading failures.

Pack Level: Equipped with automatic fire suppression systems that activate at high temperatures, precisely containing thermal runaway risks.

Cabinet Level: Incorporates an intelligent fault prediction system for real-time leakage detection, precise fault identification, and millisecond-level fault clearance.

System Level: Employs multi-level BMS protection to actively isolate risks such as over-temperature, over-voltage, over-current, and under-voltage for even safer operation.

Gravimetric energy density (Wh/kg):

Total battery energy (Wh) / Total battery mass (kg)

Volumetric energy density (Wh/L):

Total battery energy (Wh) / Total battery volume (L)

Total battery energy (Wh):

Battery capacity (Ah) × Nominal voltage (V)

Commonly used lithium - ion battery chemistries today include:

● Lithium Manganate (LMO) Batteries

● Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) Batteries

● Ternary lithium‑ion batteries (NCM or NCA)

● Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Batteries

The characteristics of different lithium-ion battery chemistries are summarized in the table below.

|

Battery Type |

Energy Density (Wh/kg) |

Cycle Life (times) |

Charge - Discharge Rate |

Safety |

Cost |

Operating Temperature Range (℃) |

Application Areas |

|

Lithium Manganate (LMO) |

90-120 |

500-1500 |

Moderate |

Moderate (prone to thermal runaway at high temperatures) |

Relatively low |

- 20-60 |

Consumer electronics, low-cost EVs, etc. |

|

Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) |

150-200 |

300-800 |

Moderate |

Poor, prone to fire in case of overcharging or overdischarging |

High |

0-45 |

3C products (mobile phones, laptops, etc.) |

|

NCM/NCA |

150-240 |

1000-2000 |

Relatively high |

NCM/NCA |

150 - 240 |

1000-2000 |

Relatively high |

|

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) |

90-160 |

2000- 7000 |

Relatively high |

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) |

90 - 160 |

2000-7000 |

Relatively high |

Among common lithium‑ion battery types, Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries stand out for their relatively high energy density, exceptional performance at both ambient and elevated temperatures, environmental friendliness, and superior safety. Owing to their excellent cycle stability and thermal resilience, LFP batteries are widely used in new energy passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles, and energy storage systems. They are also the primary choice for energy storage power supplies in data centers.

For example, Huawei SmartLi Lithium-ion Battery uses high‑consistency LFP cells. However, LFP cathode materials feature smaller particle sizes and lower compaction density, resulting in slightly lower energy density compared to high-nickel ternary lithium-ion batteries.

The primary determinants affecting the energy density of lithium-ion batteries include:

● Positive Electrode: Ternary materials (e.g., nickel‑cobalt‑aluminum NCA and nickel‑manganese‑cobalt NMC) generally achieve higher energy density than LFP due to higher operating voltages and larger capacities, but at the cost of reduced thermal stability. LFP offers slightly lower energy density but superior thermal stability, safety, and cycle life.

● Negative Electrode: Graphite is commonly used for its stable kinetics and minimal volume change but has limited capacity. Silicon‑based anodes can greatly increase capacity yet face significant volume expansion challenges that require ongoing technological solutions.

Battery packaging forms are mainly categorized into prismatic, cylindrical, and pouch types.

● Prismatic Batteries: Feature a flat, rectangular design with compact electrode stacking for high space efficiency and improved pack‑level energy density. Their rigid shape, however, may limit adaptability in complex form‑factor applications.

● Cylindrical Batteries: Utilize helical‑wound electrodes to make efficient use of internal space, yielding relatively high cell‑level energy density. Thermal management constraints on winding layers can restrict single‑cell capacity.

● Pouch Batteries: Encased in aluminum‑plastic films without rigid casings, pouch cells are lightweight, compact, and offer the highest energy density at equivalent capacities. Their customizable form factors optimize space utilization, though their flexible structure demands tighter manufacturing controls.

As a core performance metric, the energy density of lithium ion battery plays a crucial role in modern technology development. In the future, with breakthroughs in materials science and process improvements, lithium-ion battery energy density is expected to continue increasing. At the same time, it is necessary to balance safety, cycle life, and cost considerations to enable more efficient and sustainable applications of lithium-ion batteries across diverse fields.

Advantages:

● Higher energy density to meet device battery‑life requirements

● Low self‑discharge rate, minimizing stored‑energy loss

● Long cycle life, reducing replacement frequency and costs

● No memory effect, allowing charging without full discharge

Disadvantages:

● Safety risks, with potential thermal runaway under overcharging or high‑temperature conditions

● Higher costs compared to other chemistries

● Strict production‑process requirements

The service life of lithium‑ion batteries depends on various factors. Their cycle life (from full charge to full discharge) typically ranges from 5,000 cycles. Actual lifespan is closely related to operating temperature, charge–discharge rate, and depth of discharge.

The primary differences lie in their negative‑electrode materials and charging methods.

● Lithium Batteries: Use lithium metal or lithium alloys as the negative electrode. They are primary (disposable) batteries that can only discharge.

● Lithium‑Ion Batteries: Employ carbon‑based materials (e.g., graphite) as the negative electrode. They are secondary (rechargeable) batteries.